Part 1: A brief history of AI

I - The story behind a name

The conversations around "artificial intelligence" did not begin with the arrival of ChatGPT. It did not even begin with Silicon Valley conferences. And it certainly was not introduced to the public as a productivity hack, a climate solution or a sales tool: It began as a name.

1. The moment AI was born

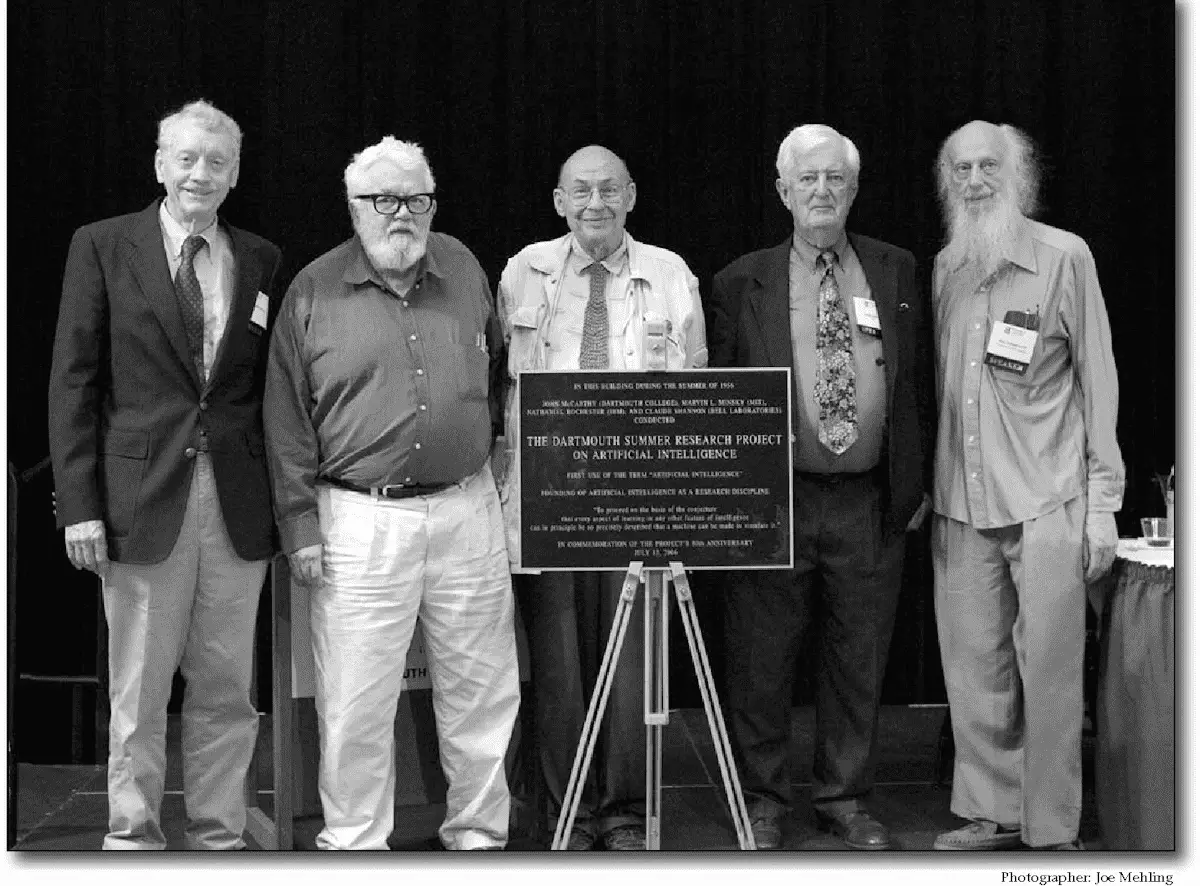

On August 31, 1955 - John McCarthy a computer scientist at Dartmouth College issued a call for papers for a Summer Study on a topic he called “Automata Studies”. Disappointed with the quality of the papers received, and after some discussions with colleagues, he renamed the topic of the conference as “Artificial Intelligence.” The phrase was meant to avoid overlap with cybernetics, attract cross-disciplinary contributions, and convey what he thought machines were capable of.

The proposal (co-signed by M. Minsky, C. Shannon & N. Rochestery) was submitted to the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence took place in the summer of 1956.

Later, in a 2011 interview, McCarthy admitted he simply “had to call it something” and even suggested “machine intelligence” might have been better. But the name stuck. The Dartmouth conference is now widely considered the founding moment of AI as a formal research field.

2. Symbolists vs. Connectionists

Therefore, after Dartmouth, AI research split into two camps:

- The symbolists who believed intelligence comes from knowing. To them, if we could encode symbolic representations of the world — rules, logic, structured knowledge — machines could reason.

- The connectionists who believed intelligence comes from learning. Inspired by the human brain, they developed neural network models that learned patterns from data.

This foundational disagreement shaped decades of research. Symbolic AI dominated early years. But connectionism resurfaced later, powering today’s machine learning and deep learning systems (Hao, 2025).

3. The Perceptron and AI's first hype

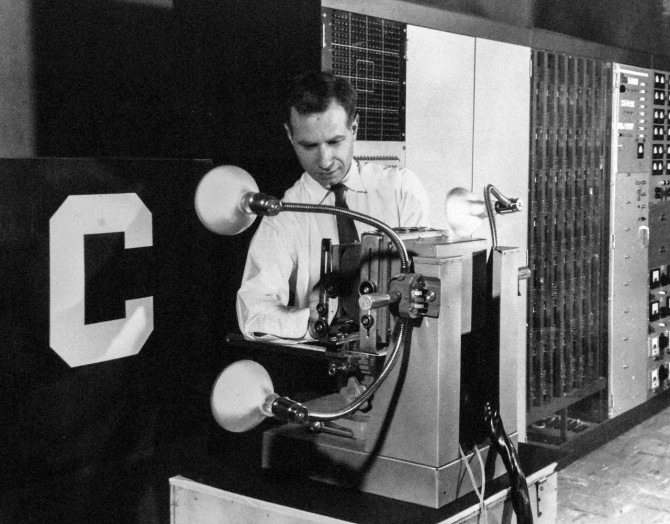

Frank Rosenblatt, computer scientist and psychologist at Cornell University built the Perceptron - a roomsize computer, single-layer neural network capable of basic pattern recognition. He described it as a step toward “machines that could see and learn like the human brain”.

In July 1958, in a brief news story, The New York Times echoed his claim declaring that the Perceptron would: “walk, talk, see, write, reproduce itself, and be conscious of its existence.”

Influenced by cybernetics, he viewed neural networks as bridges between psychology and computation, envisioning machines that could learn and make autonomous decisions. However, the perceptron had limitations, and enthusiasm eventually collapsed into what became known as an AI winter: a period of reduced funding and public interest during the 1970s and 1980s.

4. ELIZA, the first chatbot

In 1966, Joseph Weizenbaum, computer scientist at MIT, created ELIZA, a program that simulated conversation. Its most famous persona, “DOCTOR”, mimicked a therapist. Even though ELIZA had no real understanding of human emotions, people were amazed at how human-like it seemed.

Weizenbaum himself, was stunned by how quickly users formed emotional attachments:

“I was startled to see how quickly and deeply people became emotionally involved with the computer and how much they confided in it.” — Weizenbaum, Computer Power and Human Reason (1976)

ELIZA did not understand language. It mirrored it. Yet people confided in it deeply. Decades before ChatGPT, Weizenbaum had already identified a central tension: humans attribute understanding to systems that merely simulate it.

“What I had not realized is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.” — Weizenbaum, Computer Power and Human Reason (1976)

ELIZA is now seen as the conceptual ancestor of modern conversational AI (Berry, 2023) and inspired the movie ‘Her’ (2013), where Theodore Twombly develops a relationship with Samantha, an artificially intelligent operating system personified through a female voice.

II - AI in the present

1. What is AI today?

As we've seen, the history of AI is rich and covers various technologies and multiple schools of thought. To define it, according to journalist Karen Hao, think of the word “transportation”: It covers cars, trains, bicycles… but also boats and rocket-ships!

The same logic applies to the term "AI". It is an umbrella term that may include:

- Machine learning: systems that learn from data.

- Examples: Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini, which generate text and code; image generators like DALL·E and Stable Diffusion; and integrated systems like facial recognition, product recommendations, social media algorithms.

- Robotics: machines that act in the physical world.

- Examples: Robot vacuum cleaners, delivery robots, autonomous drones, and self-driving cars.

- Cognitive computing: programs that simulate aspects of human thought.

- Examples: IBM Watson analyzing legal or medical documents, or AI-powered assistants that reason through complex information.

There’s no scientific consensus on how to subcategorize AI, and classifications vary greatly. Nowadays, it seems that the term "AI" is used mostly to talk about Generative AI, which adds to the overall confusion.

2. Why is AI taking off — just now?

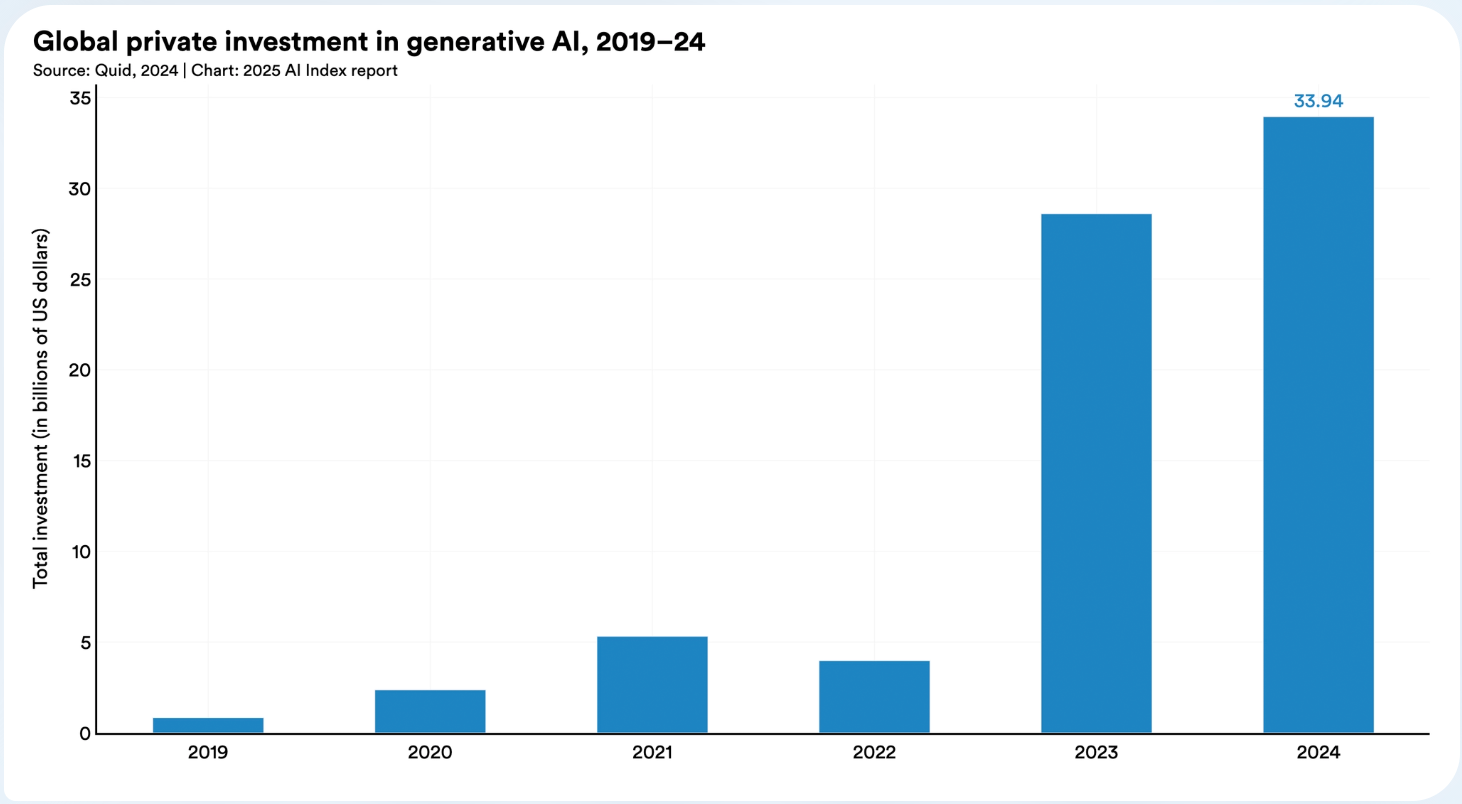

Research in Artificial Intelligence has been going on for more than 70 years. So how come that it only seems "inevitable" now? Perhaps because the story surrounding AI and especially generative AI (GenAI) is not just about a technological breakthrough.

GenAI is being deployed at scale at a moment when existing models of economic growth are faltering across much of the world. Since the 2008 financial crisis, many high-income countries have experienced slowing productivity growth, market saturation in digital products, fewer obvious frontiers for expansion and increasing wage pressure.

Therefore, AI enters this landscape as a new growth engine that promises:

- Productivity gains

- Labour automation

- New subscription markets

- New infrastructure build-outs (data centers, chips, cloud)

- A compelling narrative for investors

In that sense, AI is not just an "innovation", it is an economic strategy.

3. Who is driving the AI acceleration?

For that reason, the companies leading AI development are largely based in regions that also have faced prolonged economic stagnation since 2008, particularly the US, the EU and China.

The older generation of tech giants have reached market maturity and for them, AI offers a new expansion layer. They are embedding AI into search, cloud, productivity software, advertising, and devices:

- Meta

- Microsoft

- Amazon

- Apple

On their end, the new generation of AI-native companies (primarily US-based) are backed by massive venture capital, strategic partnerships with big tech and an "almost religious fervor" (according to Karen Hao) to deliver the next generation of AI products/services:

- OpenAI (ChatGPT, DALL·E)

- Anthropic

- Safe Superintelligence

- Thinking Machines Lab

State and corporate actors outside of the US are also investing heavily, often with strategic goals:

- EU: EuroHPC AI Factories (public AI infrastructure strategy), Mistral (France);

- China: ByteDance, Alibaba, Baidu, Huawei, Tencent;

- Other emerging hubs: South Korea (Upstage), UAE (Falcon)

These actors are funding AI development to secure military advantage, technological sovereignty, and industrial competitiveness — fast.

But what about democratic control over GenAI? Actually, AI is increasingly presented as a climate solution. How does that narrative hold up when we look at the systems powering it? Will AI save the planet?

We unpack AI’s environmental impact in our next blog. Stay tuned for Part 2.

.png)

References:

- (2025) Hao, K, Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman’s OpenAI. Penguin Group.

- (2024) Hao, K, Empowers Journalists To Unravel AI’s Complexities And Impacts, by Hessie Jones for Forbes: https://www.forbes.com/sites/hessiejones/2024/07/25/karen-hao-empowers-journalists-to-unravel-ais-complexities-and-impacts/

- (2024) Frank Rosenblatt, The Creator of the Perceptron in 1957, Quantum Zeitgeist: https://quantumzeitgeist.com/frank-rosenblatt-the-creator-of-the-perceptron-in-1957/

- (2011) John McCarthy: An interview conducted by Peter Asaro with Selma Šabanović, Stanford University: https://ethw.org/Oral-History:John_McCarthy

- (1958) NEW NAVY DEVICE LEARNS BY DOING; Psychologist Shows Embryo of Computer Designed to Read and Grow Wiser, New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/1958/07/08/archives/new-navy-device-learns-by-doing-psychologist-shows-embryo-of.html

- (2023) Knoedler, L., Knoedler, S., Allam, O., Remy, K., Miragall, M., Safi, A., Alfertshofer, M., Pomahac, B., & Kauke-Navarro, M. (2023). Application possibilities of artificial intelligence in facial vascularized composite allotransplantation—a narrative review. Frontiers In Surgery, 10: https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2023.1266399

- (2023) From Hype to Reality, Critical perspectives on AI, Pulitzer Center, AREJA & the AI Accountability Network: https://pulitzercenter.org/sites/default/files/2025-02/FromHypetoReality%20%281%29.pdf

- (2023) The Limits of Computation | Weizenbaum, Journal of the Digital Society: https://ojs.weizenbaum-institut.de/index.php/wjds/article/view/106/96

- A brief history of AI by Danielle Williams, PhD, Washington University in St. Louis: https://www.daniellejwilliams.com/_files/ugd/a6ff55_001b0152f3c5448db2d0de3859cad73a.pdf

- (1976) Weizenbaum, J; Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation. W H Freeman & Company: https://archive.org/details/computerpowerhum0000weiz_v0i3/page/n9/mode/2up

- (2025) Independent Social Research Foundation: How do we escape today’s AI? https://isrf.org/blog/how-do-we-escape-todays-ai

- Real-World Examples of Machine Learning (ML) by tableau.com. https://www.tableau.com/learn/articles/machine-learning-examples

- The 2025 AI Index Report | Stanford HAI. (n.d.). https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report/economy

.png)

.png)